Command structures

The prisoners had their own Allied camp organisation and military hierarchy, a parallel chain of command to that of the Luftwaffe. The different compounds were usually under the command of staff officers (major or lieutenant colonel). The highest military authority was the Senior Allied Officer. Between 1940 and 1944, this was the Senior British Officer (SBO) due to the high number of British POWs. With the rapid increase of incarcerated US officers, a Senior American Officer (SAO) was appointed. From 1944 onwards, both command levels were subordinated to the Senior Allied Officer, also referred to as the Allied Camp Commander by the POWs and the Germans respectively.

This self-administration ensured that discipline was maintained and that the prisoners spoke with one voice to the Germans.

German pre-camp

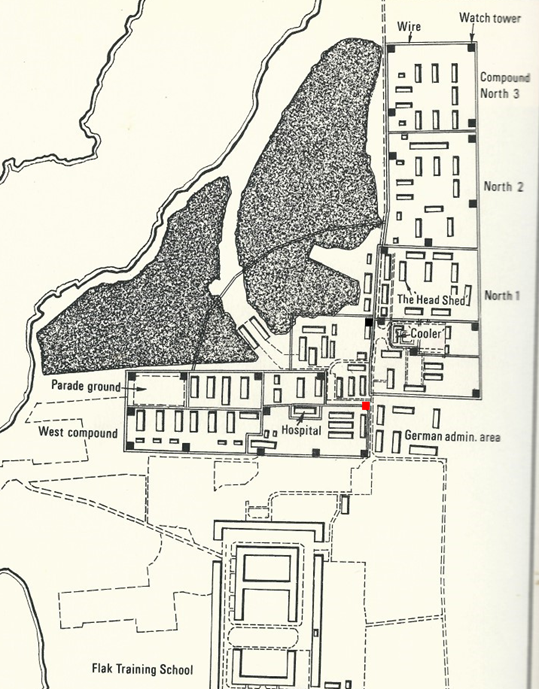

The German administrative area was located in the German pre-camp, which was fenced against the compounds. In 1944, it consisted of solid buildings including a command office, three headquarter buildings, the officers’ mess, an administration building, a parcel barrack, a coal shed, the baths (showers), a service barrack with a waste shed, a vehicle shed and the prison, which was called “Cooler” by the prisoners of war. The German camp staff amounted to 900 men. While a staff company was responsible for guarding the prisoners of war inside the camp and manning the watchtowers, so called rifle companies were responsible for guarding the outside of the large camp complex.

Soviet prisoners of war

The first half-starved members of the Soviet armed forces arrived at Stalag Luft I in the winter of 1941/1942. The Germans locked them separately from the western POWs. Their two barracks were located within a heavily secured area inside the German pre-camp (western camp complex). On average, 170 to 200 Soviet soldiers were kept there until May 1945, but there were also times with no Soviet prisoners in the camp. While the treatment of British prisoners of war and other Western Europeans as well as US-Americans was largely based on the Geneva Convention from 1929, the Soviet prisoners of war were at the lowest level of the prisoner hierarchy as “Bolshevik sub-humans” in accordance with National Socialist racial ideology. In the camp, they had to carry out the dirtiest and most degrading work and were also forced to do slave labor in the armaments industry outside the camp. They received no benefits from the International Red Cross, the YMCA or other aid organizations. In short, the Luftwaffe denied the Soviet prisoners of war any protection under international law.

Escape Attempts

Western prisoners of war had founded escape committees which organised countless, sometimes spectacular escape attempts. The first tunnel in Stalag Luft I was built by RAF officers in the summer of 1940. It was also the first RAF tunnel of the Second World War. However, it was discovered by the Germans in November 1940.

The first successful escape was made by Scottish Lieutenant Harry Burton in May 1941. The second successful escapee was RAF-Flight Lieutenant John Talbot Lovell Shore, who was obsessed with adventurous escape ideas. How often he had already told comrades: “Now I have a sure-fire plan.” This earned him the nickname “Death Shore”.

In September 1941, Shore and his friend, Bertram Arthur James, known as “Jimmy”, started with the construction of a tunnel out of a brick shed. Because of the quick work, it was named “Blitztunnel” (quick-tunnel) through which six prisoners hoped for a successful escape to freedom. The escape committee provided the necessary equipment, such as maps, tools, civilian clothes, food etc.

On October 19, however, it was only “Death Shore” who managed to escape through the partly drowned tunnel, while “Jimmy” was caught before he could crawl into.

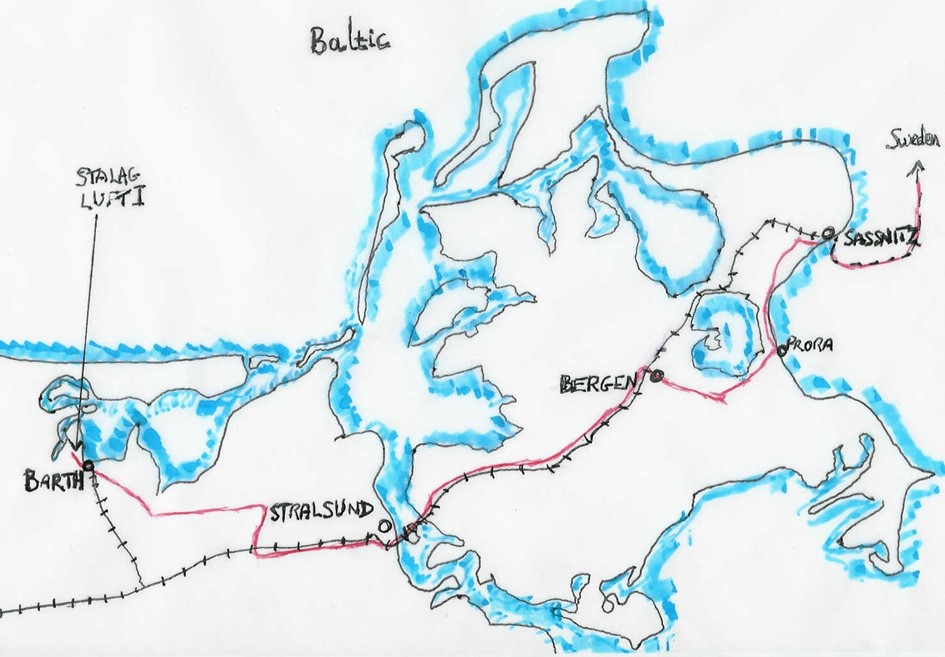

The two POWs who finally managed to escape back to the United Kingdom, Harry Burton and John Shore, walked some 50 miles each. They headed for Sassnitz harbor on Rügen Island, where they smuggled themselves onto the ferry to Trelleborg (Sweden). The authorities of the then neutral Sweden informed the British Embassy in Stockholm and the escapee could make their home run.

The escape attempt of British Sergeant John Shaw came to a tragic end in snowy January 1942. He had crawled across the snow-covered soccer pitch, was discovered from the watchtower and shot to death.

Due to expansion work on the camp all western POWs were transferred to Stalag Luft III (now Żagań in Poland) in April 1942. They left an underground with a dense network of tunnels, 45 of them in the officers’ camp alone.

Among the 76 POWs who fled during the “Great Escape” from Stalag Luft III through a 121 yards long tunnel in March 1944 were 19 who had made their first escape experience in Stalag Luft I, among them the main initiator, Roger Burshell, Wing Commander Day, B.A. James, John Dodge, Sydney Dowse and “Cookie” Long. Their freedom was short-lived and had tragic consequences for most of them: 50 officers were murdered on Hitler’s orders, including 11 former Stalag Luft I POWs. Day, James, Dodge and Dowse were transferred to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, where they managed to escape again through a tunnel in September 1944. However, they were recaptured and taken to a death block. Fortunately they were not murdered, but liberated by US troops on 2 May 1945.