Compound North III of Stalag Luft I was established in December 1944.

In the beginning of 1945, Red Army troops advanced rapidly from Poland and Lithuania to Pomerania. The inmates of the POW camps in the east were justifiably worried about their future, especially as they knew that Reichsführer SS Himmler had become responsible for controlling the POW camps in October 1944. He had ordered to evacuate the camps in the east. His idea behind this was possibly to have the prisoners as hostages or important means of bargaining chip in possible armistice negotiations with the Western Allies.

In fact, thousands of prisoners of war were driven on foot or in cattle wagons from the east to the west and south. The inmates of Stalag Luft IV in Groß Tychow (Western Pomerania, today Poland) were also affected, as it was only a matter of time before the Soviets would reach the camp. Representatives of the Swiss protecting power, who inspected prisoner of war camps, considered Stalag Luft IV to be the worst of all prisoner of war camps for Allied aircrews. One reason for this was that it was a camp for enlisted ranks which, according to the German military caste system, did not receive the same consideration as prisoner of war camps for Western Allied officers. The situation worsened after five years of war due to the catastrophic supply situation.

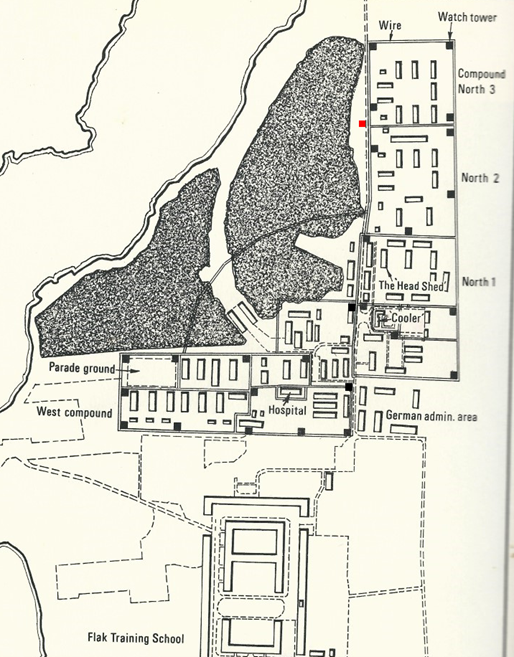

The evacuation of Stalag Luft IV began on 22 January 1945 with the transfer of 200 sick and wounded prisoners of war to Barth. On 26 January, the remaining inmates of Camp B from Groß Tychow were sent on the exhausting and nerve-racking journey in cattle wagons, which took several days. There were 60 to 70 men in each wagon. It was impossible for everyone to sit down at the same time. There were no toilets. The prisoners of war defecated in the open air when the train stopped or had to use buckets. The stench polluted the air. The journey was a nightmare for everyone. Paradoxically, there was a great danger of low-level attacks by the RAF, USAAF or soviet fighters, as the wagons were not marked with the insignia “POW” or “Red Cross”. After 7 days, they finally reached Barth station. At total around 1,500 men were transported by rail to Barth. The completely exhausted men had to walk the long way from the station to Stalag Luft I under guard, before they finally reached the camp. With the arrival of the men from Groß Tychow, the number of inmates increased to 9,000. In order to accommodate so many new arrivals, three barracks of the German fore-camp were fenced off and attached to the North I compound. In addition, two previously demolished barracks were rebuilt there. In accordance with US military tradition, the lower ranks were separated from the officers. The sergeants of Stalag Luft IV were all transferred to the North III compound, with the exception of the Jewish prisoners, who were sent to the barracks for Jewish POWs in North I. The men of Stalag Luft IV were not given cots but had to sleep on the floor or on tables. Some lay on narrow triple wooden bunks without mattresses. There was often a lack of blankets and pillows. Most of the sergeants had hoped that they would find better accommodation and food at the officers’ camp in Barth than in Stalag Luft IV. Instead, they experienced a severe period of starvation from January to the end of March 1945, as since Christmas 1944 no Red Cross parcels had arrived. As a result, they lost more and more weight and found it difficult to walk.

The enlisted men from Groß Tychow disliked their separation from the officers. The Senior Allied Officer, Colonel Zemke, as well as the three Senior Compound Officers were each fighter pilots. They were not familiar with the close relationships between officers and enlisted men that existed among the bomber crews. In this respect, the usual military caste system prevailed and this led to some friction.

Francis S. Gabreski was one of the most famous pilots in the US Army Air Force during the Second World War. He was born in a family with Polish roots in 1919, and actually wanted to study medicine like his older brother Ted, but then the suction effect of flying was stronger. He started working for a small airline. He eagerly absorbed the new, overwhelming impressions, and his first solo flight took place in December 1938.The next year, Francis was recruited by the Army Air Corps. The German war against Poland appeared in the skies of Europe. He knew that he would soon be fighting and that his weapon would be an airplane. Francis, or Gabby as he was soon known to everyone, joined the 56th Group as a young pilot in 1942. Two years later, he served as a squadron captain in his friend Hub Zemke’s famous “Wolfpack”. Francis S. Gabreski shot down 28 German airplanes. His last flight of the Second World War was his 166th combat mission. The flight ended on 20 July 1944 in the Koblenz area. His P-47 was hit by flak during a low-level attack on a German Luftwaffe air base.

After intensive interrogation in the Oberursel intelligence and evaluation center of the Luftwaffe (Dulag), he was transferred to Stalag Luft I. He stayed there from the end of 1944 and became soon Senior Compound Officer of Compound North III.

In 1951, he received a command to Korea for deployment in a “police operation”, as was initially thought. Like other former Barth prisoners, he fought in the skies over Korea and scored six and a half kills with his F-86 Sabre jet fighter. After returning from the Asian theater of war, he was honored by the American President Truman in the White House.